I am the Faithless & Perverse Generation

The Sunday of Saint John Climacus and the absurdity of the adversarial.

On the internet, outrage sells.

But it’s not just the internet: the “culture wars” that shape news and discourse capture our attention in the same way: pundits and influencers (who are often dishonest) drum up outrage that leads to engagement.

The stories that provoke this outrage can take different forms. In just the past few years, we’ve seen people angrily insist that:

the 2020 US presidential election was rigged (it wasn’t),

COVID vaccines are the mark of the beast (they aren’t),

Hollywood elites are harvesting adrenochromes from children (they aren’t), and

Russian invaded Ukraine to fight against Nazis (they didn’t).

This is a very abridged list of the kinds of nonsense that gains traction online. But I shouldn’t throw stones.

Because, in my early years on the internet, I fell for my share of nonsense.

I remember being a high schooler in the 90s eagerly following the work of Alex Joes (yup, that Alex Jones) as he “exposed” the inner workings of sinister cabals like Skull and Bones, the infamous secret society at Yale University.

After high school, I spent my undergrad years at Yale. I remember walking onto campus at the start of freshman year, eager to see these groups with my own eyes. And you know what?

I got a firsthand look at how lame secret societies really are.

Far from being some tight-knit group of autocrats who quietly rule the world, these secret societies are little more than frats that help ambitious undergrads land lucrative jobs in finance.

I learned something important: the truth is often far more banal (and boring) than the stories that aspiring influencers tell to attract attention.

But admitting that I’d been duped wasn’t easy…

I can still recall the moment when I stopped short and realized—with a little horror and a lot of embarrassment—that I had spent years “researching” conspiracy theories that were, at best, wild exaggerations of the truth.

And, at worst, they were completely made up.

So why is this on my mind?

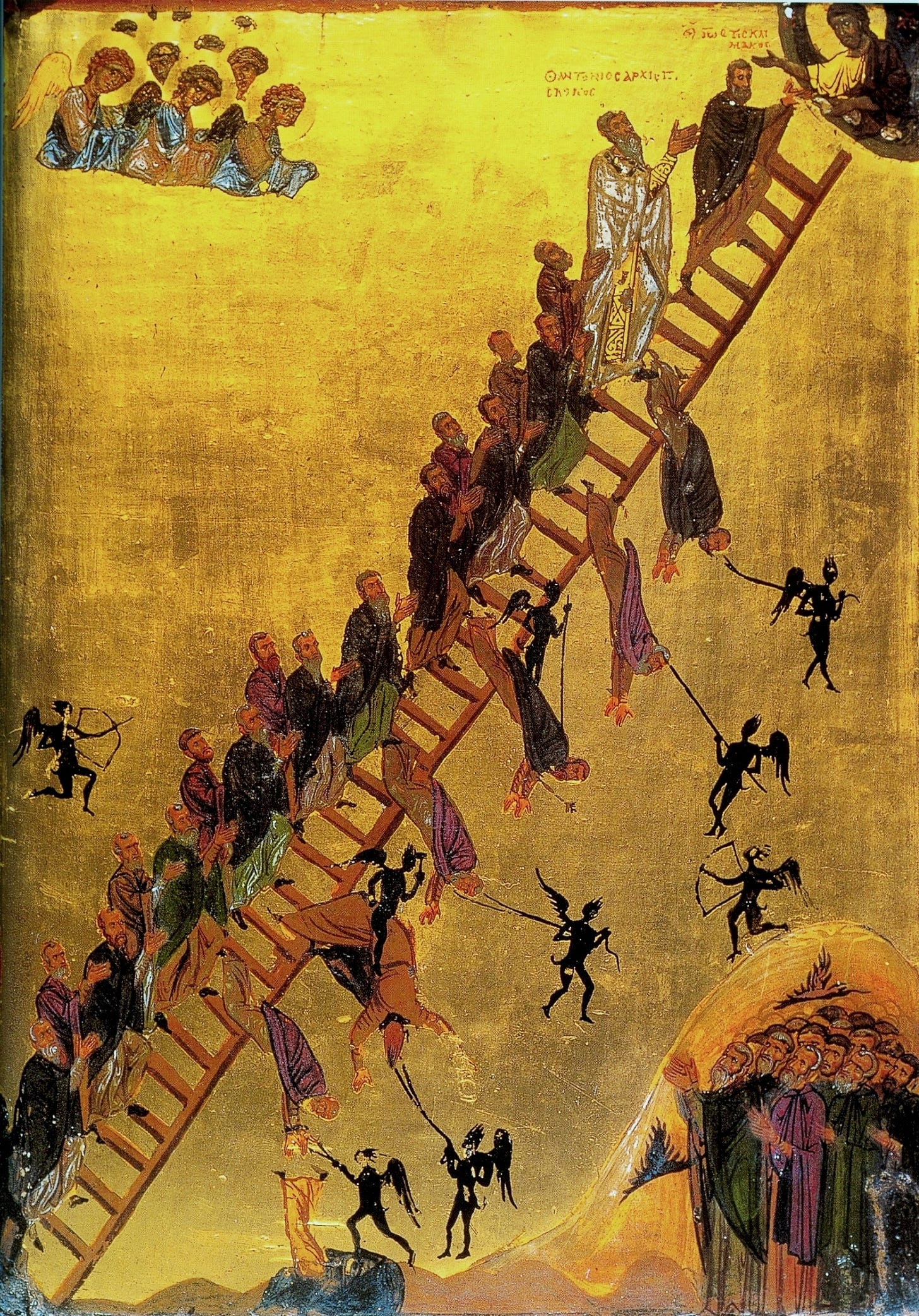

Well, the Sunday of Saint John Climacus is supposed to help us chart the path to holiness—the path up the ladder, so to speak, as we progress in repentance and know Christ more fully.

But it’s also worth understanding what happens when we climb down the ladder—when, instead of starting with repentance, we divert our attention to focus on what’s wrong with others.

Because outrage at what’s wrong with others sells.

And make no mistake, we Orthodox Christians are often first in line to feast on it.

So let’s start at the beginning: with a look at why certain content satisfies our hunger.

And, if you’ve been following along the past few weeks, you may have an idea where we’ll begin…

Authority in a Secular3 World

We’ve already seen how, in our Secular3 world, meaning is something the individual creates for himself.

Because truth is not a thing we share, a bedrock upon which we all stand. Rather, truth is what I make of it.

And this affects the media we consume.

Because, when a post goes viral on social media warning us that COVID vaccines are magnetizing people, it’s not because we trust the journalist who is reporting the story or the rigorous research that led to the conclusion.

No, the post goes viral because it says something we want to be true.

Here in Secular3, we don’t look to journalists with a long career built on honesty and integrity. We don’t look to research that emerges from a peer review process that pokes holes in shoddy methodology.

We just share things that seem true to us.

It’s why, as a high schooler, I ate up stories about secret societies and global conspiracies. I mean, the only evidence I had came from a guy who would later claim that the Sandy Hook school shooting was a “false flag.” But I wanted the conspiracy to be true.

Want another example? What about Dominion’s lawsuit against Fox News?

(Don’t worry, I’m not going to make a partisan point.)

Internal documents reveal that Fox continued to report that the 2020 election was rigged—even though they knew it wasn’t—because they were afraid their audience would switch to another network willing to feed them the “news” they craved.

In other words, people weren’t judging the quality of news based on its source. They were judging the source based on the “news” it broadcast.

Because the individual is now the source of authority.

By contrast, when Walter Cronkite reported on the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, people believed that humans walked the lunar surface (rather than share conspiracy theories about how the landing was faked).

When Walter Cronkite reported on the Watergate scandal in the early 1970s, people believed that the Nixon administration had done something criminal (rather than defend a politician no matter the evidence).

In years pas, certain individuals and institutions had an authority that allowed them to share unpleasant or hard-to-believe truths with the public.

But authority is no longer found outside of individual choice.

Because, here in Secular3, people don’t tune into the news to learn anything. We tune into the news to hear what we already believe to be true. And to the extent anyone has authority, it’s because they’re willing to cater to those base impulses and answer the important question:

Who will tell us what we want to hear?

Now, this isn’t a problem unique to the right: it’s a problem for all of us here in our postmodern age where every individual is the maker of his own private meaning and reality.

(And this insight might help you better understand my piece on contemporary apologetics from a couple weeks ago.)

But all of this raises another question. Because, if we’re all seeking what we want to hear, well…

What exactly do we want to hear?

The Direction of Our Outrage

If you’ve spent any time with Scripture or the Fathers, you’ll notice a pattern in where Christians are called to focus our attention—especially when it comes to addressing sin.

We’re each called to focus on:

our personal sin,

the sin of our fellow Christians, and

the sin of the wider world.

That order is deliberate. My attention should first be on my own sin. After all, we’re called to confess ourselves as “the first among sinners” (1 Timothy 1:15).

Next, we can turn to the sins of our brothers and sisters in the Church, those who “are no longer strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God” (Ephesians 2:19). These are the people who’ve already accepted Christ and been baptized into Him—people who should be living transfigured lives based on their place in the household of God.

But this attention to the sins of others in the Church can only happen under certain circumstances. As Father Tom Hopko famously put it in his list of 55 Maxims, “give advice to others only when asked to do so or when it is your duty to do so.”

Finally, we are most gentle on those who have not yet fully entered the household of God. They have not yet accepted Christ and so can’t be held to the same high bar by which we Christians will be judged. We see this in Scripture: for example, Christ overturned the tables of the money changers in the Temple while Saint Paul approached the pagan Athenians with gentleness (reserving his most pointed words for his fellow Christians).

But we tend to have it backwards. In our Secular3 world, we focus on:

the sin of the wider world, and

the sin of our fellow Christians.

(And maybe we’ll pay lip service to our personal sin.)

Why?

Because the individual is the source of meaning.

Here in Secular3, we don’t really believe in the power of divine action so my individual choice is the foundation of what’s true and what’s not.

And some Scripture can help us understand…

The Faithless and Perverse Generation

In the Gospel reading for the Sunday of Saint John Climacus, which is from Mark 9, the disciples seriously drop the ball.

Earlier, in Mark 6, Jesus sends His disciples out in pairs to heal the sick and minister to people. He even gives them authority over unclean spirits.

And, for a while at least, the disciples went out to the people and did exactly that:

They went out and proclaimed that all should repent. They cast out many demons, and anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them. (Mark 6:12-13)

Yet, in the space of a few short chapters, something happens. The disciples, who used to work great wonders in the name of Jesus, suddenly fall short.

And we see the consequences of this when one man steps out of the crowd, kneels before Jesus, and delivers some bad news:

The disciples couldn’t help his son.

“Teacher, I brought my son to you, for he has a dumb spirit; and wherever it seizes him it dashes him down; and he foams and grinds his teeth and becomes rigid; and I asked your disciples to cast it out, and they were not able.” (Mark 9:17-18)

Jesus responds by turning to His disciples and calling them a “faithless generation.” In Matthew and Luke’s version of the story, He calls them not just “faithless,” but “perverse.”

This language calls back all the way to Deuteronomy 32. In a passage known as “the Song of Moses,” the great prophet calls the people “a perverse and crooked generation.” He describes how they consistently turn their back on God despite all the wonders He works for them.

The Lord freed them from slavery in Egypt, and they complained. He fed them manna from heaven, and they asked for meat instead.

Again and again, the people prove self-absorbed and forgetful of God, which is why Moses left his Song as a sharp reminder for the people.

And yet, years later, Jesus identifies another faithless and perverse generation: His very disciples.

But what made the disciples faithless and perverse?

A reliance on themselves…

Self-Reliance and Secular3

The Lord’s disciples believed they could heal the boy they encountered in Mark 9. You can almost hear the surprise and confusion in their voices when the disciples take Jesus aside and ask Him: “why could we not cast it out?”

To their surprise, the Lord’s response is simple and to the point: "This kind cannot be driven out by anything but prayer and fasting" (Mark 9:29).

Now, Christ isn’t saying that prayer and fasting are magical tricks that would give the disciples power to do superhuman things.

Rather, prayer and fasting are ways we acknowledge that “it is time for the Lord to act” (Psalm 119:26).

Because prayer is how we reach out to God. It’s humbly realizing the limits of our strength and ability and asking God to act.

And fasting is how we putting our own will to death as we invite God to act in and through us.

In other words, prayer and fasting are about emptying ourselves so we can be filled with the Holy Spirit to guide our words and our actions.

It’s what we explored in our last post on putting our false self to death.

So, when the disciples ask why they couldn’t cast out the demon, they’re asking the wrong question…

Because, when the Lord points to prayer and fasting—to practices that open our lives to divine action—He’s really asking, “why didn’t you ask me to cast out the demon?”

Why didn’t you let me act through you?

But again, here in Secular3, this is hard to hear…

Because the postmodern, buffered self is resistant to meaning outside its own choice. Repentance means submitting yourself to Someone else. The ascetic life of the Christian means being open to the possibility of Someone else living in and through you.

It is not longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. (Galatians 2:20)

And, to the individual who creates meaning for himself, that’s terrifying.

So, rather than direct my outrage at my own sin, I rail at the world. I divert my attention and energy to the faults I see in others, foaming at the mouth like the possessed boy in Mark 9. I obsess over cultural trends I despise. I openly mock presbyters and hierarchs, if not entire jurisdictions of my fellow Orthodox Christians.

I’d rather critique the demoniac than open my heart to Christ so the demoniac can be healed. I’d rather remain smug in my own superiority than fall at the Lord’s feet and die to my pride and self-reliance.

I’d rather proclaim the sins of others than admit that I am the faithless and perverse generation.

And so, I descend…

“Why could I not heal him, Lord? Because I am not you.”

Remember, there are three things we can focus on:

our personal sin,

the sin of our fellow Christians, and

the sin of the wider world.

If I neglect my own sin, I will never become a temple of the Living God. I will be nothing more than a Christian in name only, a clanging gong that the Lord will spit out on the Last Day.

(Even if I attract a lot of internet attention in the meantime.)

May we focus our energy and attention on our own sins, and have little (if any) left for the sins of others—unless we’re asked or it’s our duty to look to those sins.

Because, while we’re called to climb the ladder, we can easily descend it.

Thank you. I appreciated this reminder of where my focus for repentance needs to be.

Thank you for your insights and perspectives .

Very helpful for me .